Rowing the Mississippi River…in Winter

Guest Blog by Iowa River Citizen, Melissa Serenda

It was a little before 9am on Valentine’s Day that I passed Lock & Dam Number 19 at Keokuk, and just a bit later that I rowed past the confluence of the Des Moines River with the Mississippi, signaling that I had left Iowa waters and moved into Missouri. The air temperature outside was -8 degrees F. I was wearing shorts and a tank top.

In previous years, I have rowed on the Iowa River with Hawkeye Community Rowing, where our rows are limited to the navigable stretch between two roller dams. Rowing on the water can be a delicate business: you can’t row when it’s too cold, or too windy, or too rainy or foggy, or when the water is too high and fast. You need fairly costly equipment, and it’s generally advisable to row with companions and a coach who can fish you out in the event of an “out of boat experience” (of which I have had one, an event equal parts hilarious and horrifying). The erg, while less scenic, cares not for vagaries of weather or water, and can be done at any hour. Not to mention there is no risk of running into stumps in the dark, or those tree branches dangling over the water that somehow reach out to grab your quad-mates three times in one summer as you steered in the bow.

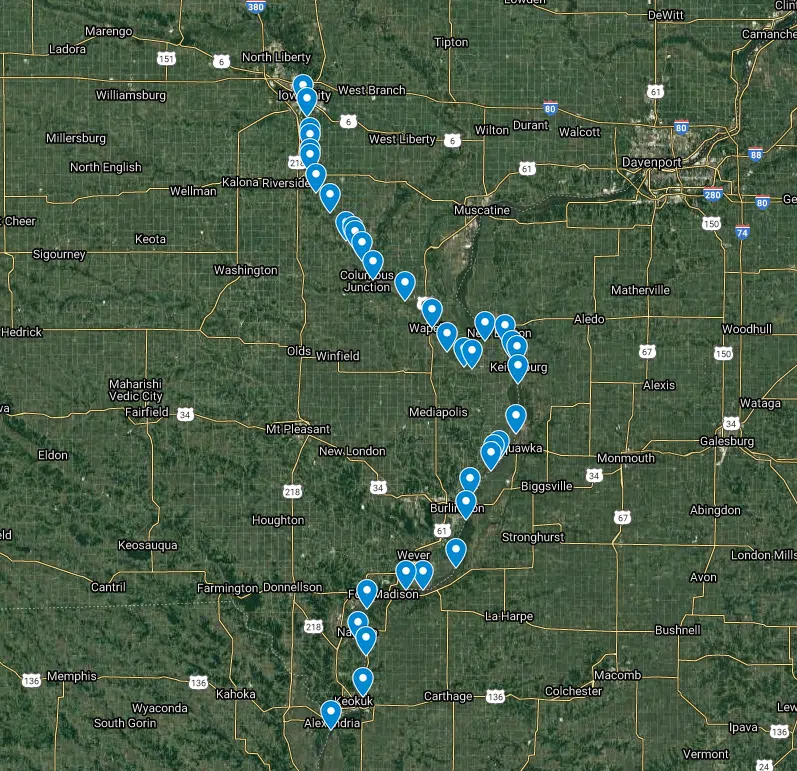

When I first “put in” at Sturgis Ferry, I had no idea what the trip would be like.

I’ve visited several cities along the Mississippi: Minneapolis, Dubuque, the Quad Cities, Burlington, Hannibal St. Louis, Memphis. I’ve taken a few hours-long leisure cruises on the river from those cities. But I’ve never traveled any distance along the river itself. Tracing the Iowa River south and east, I saw how few cities and towns there were alongside it. It was narrow and twisty, and I was able to finally place some of the towns and landmarks I’d heard over my nearly 25 years living in eastern Iowa.

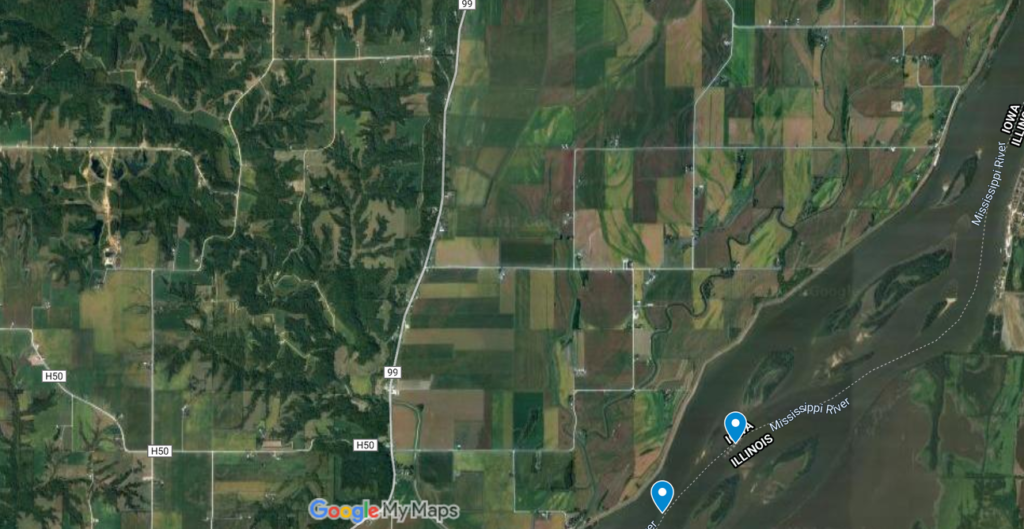

The English River, which joined the Iowa east of the little town of Riverside. I saw the patchwork of agricultural fields, straight-edged and sharp-cornered, around which round the somewhat fractal and untamed greenery that indicated wooded streams and waterways. It is easy to see each of those riparian fingers as a capillary carrying water (and nitrates, pesticides, and anything else applied to those vast ag monocultures) flowing off those ag fields into the rivers that eventually reach our nation’s aorta, the Mississippi.

“Every point along the river touches something else. It’s a rope of innumerable fibers, each of which can be followed back to some connecting point of history, of geography and nature, of our own memories and travels.”

Near the little town of Columbus Junction, the Iowa meets the Cedar River. I had assumed the name of the town came from that meeting of the two big waterways of eastern Iowa, but a minute of research described the naming as a result of the intersection of two railways in 1870. Now, the satellite view of the town reveals a huge industrial scar north of the town labeled “Tyson Foods Inc.” with several large constructed basins of liquid, nestled right along the north bank of the Iowa River flowing by.

Seeing the Cedar, I recall decades ago learning about the existence of paddlefish for the first time: a photo from the Cedar Rapids Gazette, a fisherman holding his massive, prehistoric-looking prize, caught near the Five in One Dam. It was such a bizarre-looking fish, with its long, flat rostrum and vaguely frowning mouth. To imagine such a fantastical thing living its life down there in the brown water of the river, mostly unseen and unknown by those above the surface, sparked the first inkling of a connection in me with rivers and their inhabitants.

Further down the Iowa, past what appear to be sandbars alternating along the way, the river twists sharply to the north. Ghosts of earlier twists and turns of an untamed river can be seen in those last dozen miles between Wapello and the Mississippi. On January 24, I imagine being spit out from the cozy Iowa into the comparatively vast, storied waters of the Old Man River as I plot my latest distance of 6000 meters. I picture myself in a narrow boat lurking near the shore and watching lumbering barges go by, doing their river business as has been done for centuries.

As I continue down the river, I marvel at the many ways we have changed the landscape, imposing those straight lines onto a world that eschews them. What impositions were made on the land to force it into those straight lines? How long can they be accommodated, holding out against the combined forces of nature and history struggling to reassert the winding wildness to which it is accustomed? Hovering north of Burlington, one can see a stark demarcation along Highway 99, west of which some semblance of that unconstrained, semi-wooded world remains, while east of the highway there is an orderly, flat patchwork, with an unnamed domesticated waterway one of the few–very constrained–nods to the landscape that was.

Near Burlington, the river is dotted with a series of large islands, multiple channels running around and through the landmasses. I chart my course along the dotted line that signifies the border between Illinois and Iowa. I see the border, normally near the center of the river, sidle up next to the Illinois shore and realize I’m passing through a dam just north of Burlington. My first dam! Lock and Dam No. 18, completed in 1937. I examine photos of the lock, a slender compartment to safely pass around the massive dam constructed to impose our human will on an untameable river. It doesn’t look like much from the sky–I likely would have skipped right over it on the map, assuming it to be another bridge over the river if not for the telltale movement of the borderline.

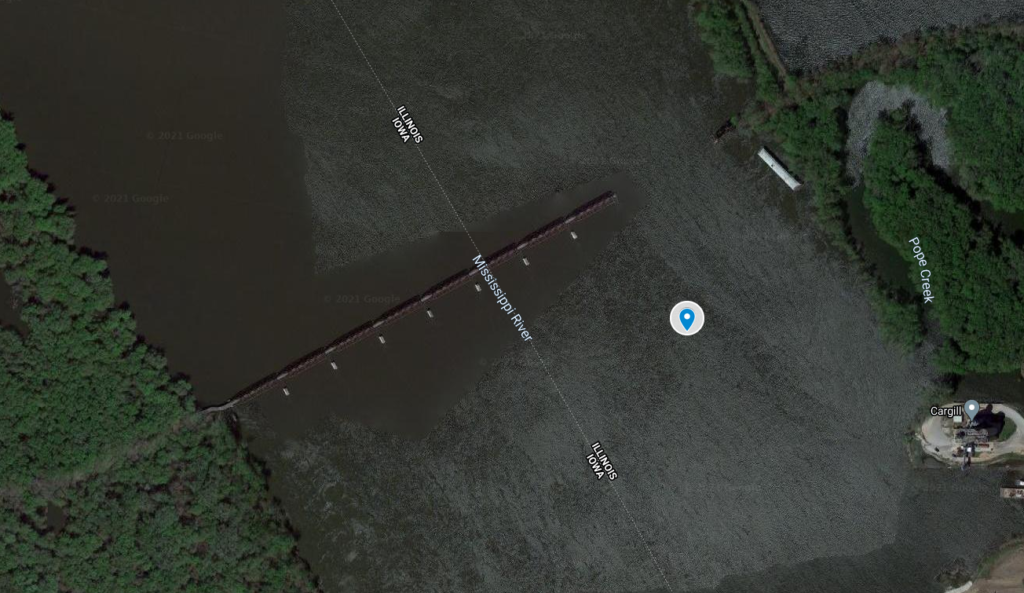

Encountering the lock and dam sent me exploring back upriver to see whether I had missed an earlier dam (I hadn’t; Lock and Dam No. 17 was a little ways north of where the Iowa River joined the Mississippi), where I noticed an odd structure jutting out partway across the river. It looked like a bridge, but missing a chunk near the Illinois side. This turned out to be the Keithsburg Railroad Bridge, active between 1909 and 1971. The missing portion had fallen into the river after a fire sparked by young hooligans playing with fireworks; it was cleared away but the rest of the bridge was left standing, a vestige of last century’s transportation network.

By February 9 I had just passed Fort Madison, and was looking forward to finally reaching Keokuk and moving beyond the watery borders of Iowa. Here I found Lock and Dam No. 19, with the lock on the Iowa side this time. Construction on the dam was completed in 1913, just before the start of the Great War in Europe. Before this dam was constructed, the section of river between Nauvoo, IL and Keokuk contained the Des Moines Rapids, in portions of which the river depth was less than 3 feet. The construction of the dam eliminated the shallow rapids and opened the river to river traffic; it also provided (and continues to provide) electricity through the power of the river.

Just beyond the orderly grid of Keokuk’s streets, I meet up with the Des Moines River. I trace its path back west and north, discovering along the way that Iowa, like Ohio, has a town named Chillicothe. A rather unearthly aquamarine pool draws the eye, right next to the sprawling lesion of the Martin-Marietta Durham Mine. I reach the Red Rock Dam, beyond which is the massive, man-made Lake Red Rock. It looks unhealthy from orbit, like an artery bloated above a cinch-point. Articles claim the dam was necessary to control flooding downriver. I can’t help but wonder what restrictions the river would impose on us to prevent damage downriver if it had the opportunity.

When I began this journey, I thought it would be a novel way to motivate my workouts, logging meters and working toward a distance goal for the year. But with each point I plot along the journey, I see new parts of our world and explore the nodes of history and culture that are found along the Mississippi and throughout the entire watershed. Every point along the river touches something else. It’s a rope of innumerable fibers, each of which can be followed back to some connecting point of history, of geography and nature, of our own memories and travels. I marvel at how much there is to see from the seat of my erg in the basement, and can’t wait to see what I will find around the next bend.

Blog submitted by Iowa River Citizen Melissa Serenda. Thank you, Melissa!

Email your story of how you are enjoying our Mississippi River to info@1mississippi.org

Join our

COMMUNITY

And Get a Free E-book!

When you sign up as a River Citizen you’ll receive our newsletters and updates, which offer events, activities, and actions you can take to help protect the Mississippi River.

You’ll also get our free e-book, Scenes From Our Mighty Mississippi, an inspiring collection of images featuring the River.

Step 1

Become a River Citizen

Yes! The River can count on me!

I am committed to protecting the Mississippi River. Please keep me informed about actions I can take to protect the Mississippi River as a River Citizen, and send me my free e-book!, Scenes From Our Mighty Mississippi!

Step 2

LEARN ABOUT THE RIVER

We protect what we know and love. As a River Citizen, you’ll receive our email newsletter and updates, which offer countless ways to engage with and learn more about the River. You can also follow us on Instagram, Facebook, X (Twitter) , and YouTube, where we share about urgent issues facing the River, such as nutrient pollution, the importance of floodplains and wetlands, and bedrock legislation such as Farm Bill Conservation Programs.

Step 3

Take Action

There are many ways you can jump in and take action for a healthy Mississippi River. Our 10 actions list includes simple steps you can take at any time and wherever you are. Check out our action center for current action alerts, bigger projects we are working on, and ways to get involved.