My Mississippi River

There are so many ways to connect with our Mississippi River’s people, land, water, and wildlife. Our friend and Mississippi River Network member, Dean Klinkenberg, aka The Mississippi Valley Traveler, is known for his guidebooks and storytelling. Recently, we collaborated with Dean on a project to uplift the various ways people engage with the River and the impacts of the River on people and communities. Here’s what Dean had to say about the project:

“One of the original goals for this project was to show off the diversity of people who engage with the River, and I’m pleased with how it turned out. I interviewed folks from the length of the River (4 from the upper river, two from the middle, two from the lower, and two who represented the whole river). Men and women are represented equally, and I talked with people from various racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Ultimately, this was about showing off the many ways we engage with the Mississippi. These profiles cover quite a spectrum: fishing, river-inspired art, paddlers, river angels, guides, advocates, conservationists, people with a strong spiritual connection to the river, and even the founder of a popular river-themed Facebook group. It’s a nice group of river people, and I barely scratched the surface!”

We hope you enjoy these stories! Do you want to offer a “my Mississippi River” story or know someone we should connect with? Please reach out to us at [email protected]!

Norman Schager

Tags: photography, Facebook, social media

Norman Schafer lives near the Mississippi River but just can’t get enough of it. In this post, he talks about why he founded what has become a hugely popular and drama-free FB group where people share photos of the river, a bright spot in the social media landscape.

In 2014, Norman Schafer started a Facebook group to showcase pictures of high water on the Mississippi River. When the waters receded, he realized that a group called Mississippi River Flood Photos was going to have a limited appeal, so he dropped “flood” from the name. Over the next couple of years, the group steadily added a few thousand followers. In the last couple of years, though, a couple of popular posts sparked exponential growth, propelling the group’s membership to over 165,000!

Norman has lived his entire life near the Mississippi River in southeast Iowa. He has worked on the river for over 30 years. While he knows his part of the Mississippi well, the Facebook group shows off the entire river and the river’s changing faces throughout the year. “A lot of people love the river, and they want to see everything up and down the river that you would have to drive to see. Well, here you don’t have to drive anywhere. You can just log on and see everything.”

The images of the river change with the seasons and the perspectives of people who post. Pictures of bald eagles are common in winter. Lots of colorful trees show up in fall. Barge pilots post pictures of their view of the river. “From captains, to fishermen, to cabin owners, photographers, there’s just multitudes of people. And we all get together in one room and just talk, or share.”

The group has a couple of other moderators to make sure people follow the simple rules, which are basically be nice, don’t swear, don’t make political posts, and say something about the Mississippi River.

“It’s just a really good group… Everybody just gets along for the most part.”

For Norman, the Facebook group is a labor of love. “I don’t get a dime from this, just the enjoyment of creating probably the world’s biggest river group… It’s just sharing with people. That’s what it’s about. I enjoy that people actually enjoy the group and have fun with it.”

Jorge Abadin

Tags: poetry, New Orleans, inspiration, deep thoughts, peaceful

For native New Orleanian Jorge Abadin, inspiration is just a bench in Crescent Park away. “I’d bring my maté out there (he studied in Argentina for a while). I’d bring a book and something to write with.” He’d sit on that bench and let his mind wander as he watched the Mississippi River flow. Sometimes, thinking was enough. Other times, he translated his thoughts into poems.

Even though he grew up in New Orleans, it took him a while to find his way to the river. Not until he was a college student, in fact, in Baton Rouge at Louisiana State University. He worked as a delivery driver to earn some cash and regularly crossed up and over the Mississippi. It got his attention. As he got to know downtown Baton Rouge better, he drifted toward the riverfront where he’d find a bench to sit for a while and watch. When the river got low, he found a new spot—unknown to most people—where he could hang out, a spot that he sometimes shared with friends.

In Baton Rouge, he found that time spent next to the river helped him clear his head. “Going out to the river was always a place to calm down… to disconnect from campus and just take it slow and take it easy and enjoy the water.”

Once the river had his attention, he sought it out in new places. He found a nice patch of grass at the end of the Fly in Audubon Park, a place that entices folks to sit, eat, relax, hang out, and watch the tugs and barges drift by.

He may also wander over to Algiers Point on the bank opposite from the French Quarter, where his mind will sometimes fill with the music of an old gospel song, such as I’ll Fly Away, a song with a meaning that has evolved over time and generations. One line in the song references flying to a home on God’s celestial shores. “When I think about it [those lyrics], I’ll think about Algiers Point: sitting out there in the grass at Algiers Point on a sunny day, a little windy on the river, a barge passes by; you’re just content. This is God’s celestial shore.”

Crescent Park, though, remains special to him. “It’s a nice little description of New Orleans, of ruin and beauty coinciding together on the river.” On that bench near the Mandeville Shed, not far from willow stands growing around abandoned wharves, he’d think about what the Mississippi represents.

“The river just for me has always meant opposites. It means everything and it means nothing. It’s life, it’s death. It’s beautiful, it’s ugly. It’s clear, it’s muddy. It’s rough and calm at the same time.”

In New Orleans, “everybody loves the river. They hate it—it’s a beast—but it’s also so beautiful.”

One of Jorge’s river-inspired poems is called “A Response to Berthe D’s “Love” — A River Live Session.” Here’s a sample:

Love is

Sky so blue cloud so white, believe the cornet dream,

Red beans and ricely yours, a smile now mainstream.

A French Quarter trombone, flying away with blues,

A dancing resting place, for a ramblin’ man’s booze.

Love is

A moon that outshines sun, Maple drips Rebirth band,

God’s celestial shore, living in gloryland.

Feeling my lovely home, watch a steamboat joyride,

Hearing all of these sounds, down by the riverside.

Sharon Day

Tags: water is life, Indigenous activism, awareness, spirituality, respect

In 2013, Sharon Day and a group of indigenous women known as Nibi Walks embarked on a months-long journey, walking along the Mississippi River to honor and reconnect with the water. Their act of devotion inspired others to make offerings and take care of the water in their own ways, emphasizing the importance of protecting our natural resources.

Tales of personal connections with the mighty Mississippi River and its profound significance to us: Day 1.

On March 1, 2013, Sharon Day gathered with four other Native American women and two Native American men at the Mississippi Headwaters. It was a cold morning, just six degrees (F), when they dipped three five-gallon water jugs into the emergent river. Josephine Mandamin, the Anishinaabe woman who founded the contemporary water protector movement, led a prayer. After each person took a sip of the crisp, clear Mississippi River water, they walked. They walked along the Mississippi every day until May 3—through a blizzard, rainstorms, and sunny days—until they reached Fort Jackson, Louisiana, near the river’s end. Each day they paid their respects to the river.

At Fort Jackson, as a light mist enveloped them, Josephine Mandamin once again joined the group in prayer. They offered a tribute of asema (tobacco) to the river and reunited the waters from the river’s source with her lower self. “We wanted to give her a taste of herself,” Day said. “This is how you began, healthy enough for us to drink. And this is how we wish for you to be again.”

A wave rolled into shore and lapped around their ankles, followed by another one, then two more, the fourth one washing up to their knees. “It was like being kissed by the river.”

In many indigenous communities, including the Ojibwe community in which Day grew up, women take care of the water. The Mississippi River walk was one way that Day and other indigenous women honored the water and strengthened their connections to the river.

Day founded a group called Nibi Walks (nibi means water in the Ojibwe language) to continue the practice of tending to the water. She has since led walks along the Missouri, Ohio, and other rivers. Those walks inspired others to gather on Sunday mornings and make regular offerings to the river in places as far strung as Grand Rapids, Minnesota, the Twin Cities, La Crosse, Wisconsin, St. Louis, even occasionally in Memphis and Baton Rouge.

Not everyone is going to walk hundreds of miles to honor and connect to water as Day has done. But we can act in our own ways. “If you cannot walk with us,” Day said, “then just make an offering every day to the water, to the land, to all that there is, and that’s all we can hope to do.”

Thanks to 1 Mississippi for providing the funding and inspiration that made it possible for me to collect stories about #mymississippiriver!

Photo by John Kaul

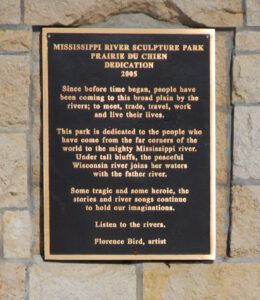

Florence Bird

Tags: art, history, sculpture, inspiration, confluences

“I stood in the sand next to the Mississippi River and wondered who had stood there before me.”

Even though her family has deep roots in Wisconsin, sculptor Florence Bird knew nothing of the old Mississippi River town of Prairie du Chien until twenty years ago. During her initial trip, she went to St. Feriole Island—to the area where Prairie du Chien began—where a moment and a thought would change her life.

“When I first got to Prairie du Chien and I was standing there by the Mississippi River, I thought, ‘This is the river of Mark Twain, and steamboats.’ It was a magical place for me. That’s when I wondered who else stood here.”

That moment, that single thought, inspired a bold idea for a project that will take years to complete: to create sculptures of some of the people who have stood in that very spot over the last 10,000 years.

Florence developed a plan for 26 sculptures in total, all of them selected because they had a hand in shaping the history of the area around the confluence of the Wisconsin and Mississippi Rivers. When completed, each sculpture would be given a home in the Mississippi River Sculpture Park on St. Feriole Island.

She began by crafting a small clay mold of each figure. All 26 of those are now finished. When she has raised enough money to complete a full sculpture, she works with a foundry in Milwaukee to bring it to life. The factory crafts a Styrofoam model, which she then details in clay, then sends it back to the foundry for casting in bronze.

She began the project by creating a sculpture of Black Hawk, the Sauk leader. It was installed in 2005. The sculpture of local legend and basket making artisan, Emma Big Bear, was installed in 2011. Bird has completed six sculptures as of 2022, with three more coming soon, including sculptures of Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet that she hopes to have in place to commemorate the 350th anniversary of their journey down the Mississippi River.

The area around Prairie du Chien, near the merging of the Mississippi and Wisconsin Rivers, has a long history as a confluence of cultures, too. Bird’s sculptures offer one way for us to reflect on and appreciate that deep history.

Learn more about Bird’s sculptures here: https://sites.google.com/view/mississippirsculpturepark/home

Cory Maria Dack & Sarah Lent

Tags: paddling, guide, perseverance, visibility, community, representation

Every year, a few dozen people push off from Lake Itasca and paddle their way toward the Gulf of Mexico. As a group, the paddlers skew young and male and white. Cory Maria Dack is one of the exceptions. While Cory grew up in Duluth, Minnesota, she was born to an indigenous Ecuadoran mother. As a child, she wasn’t much of an outdoorsy person. Her family didn’t have the money to travel to national parks or send her to summer camps. It wasn’t until college that she had her first significant experiences with the outdoors, when she began working as a counselor at a summer camp in Minnesota’s Arrowhead region. Once she got a taste of working in the outdoors and helping others get comfortable with it, she was hooked. For sixteen years she has worked as a guide in places from northern Minnesota to Yellowstone National Park to Costa Rica and Ecuador.

In 2018, she guided college students down the Mississippi River as part of Augsburg University’s River Semester program. Those 100 days on the river sparked dreams of exploring the entire river herself, of paddling it from north to south. “It was an idea that took seed,” she said, “and I nurtured it as I did other things, and the idea just kept growing and growing until I felt like I wanted to go.”

In 2022, that dream became a reality. “I talk about my life as a river, and I feel like that’s my river flow. I feel like my river has just very slowly and naturally flowed to this type of trip.”

On August 21, she and her friend Espoir pushed into the Mississippi River from Lake Itasca and began the 2,500-mile paddle to the Gulf of Mexico. The early days of the paddle made a deep impression on her. “The Mississippi in her infancy, she’s so pristine, and she’s so gentle, she’s so beautiful. She’s fragile and powerful at the same time. And you want to protect her, but she’ll also kick your ass at the same time.”

Espoir exited the trip at the Quad Cities, and Sarah Lent joined Cory at Hannibal for the rest of the paddle to the Gulf. Sarah was an adventurous child—she was one of the kids you’d find climbing a tree or over rocks—but she didn’t really get hooked on the outdoors until she got older. And then she really got hooked. She’s worked as a kayak guide in Alaska and served with AmeriCorps at Glacier National Park. She had just been laid off from a job in 2022 when she found out that Cory was looking for someone to take Espoir’s place in the canoe. She reached out to Cory right away.

Cory, Espoir, and Sarah have faced their share of challenges paddling down the Mississippi. Progress was slower than Cory had hoped, and the trip continued into the early days of winter. All along, Cory had feared paddling on the Mississippi in winter. But she and Sarah adapted. They got plenty of help from river angels along the way and upgraded their gear to help them cope with the cold.

As they made their way south, they discovered a remarkable group of people who live along the Mississippi. “What we’ve had each night,” Sarah said, “and each day is just community along the river. It’s getting to meet different river angels and people that have taken us in and shared their stories of… why they love the river.” They were touched by the number of strangers willing to help them out, people who cared deeply for the Mississippi. “What I’ve learned is how much love there is for the river,” Sarah said.

But a few people judged their fitness for a long-distance paddle and their outdoor skills on assumptions based on their gender or skin color and not on their experience and skills. They heard patronizing comments that contrasted sharply with the encouragement the same people had made to the white male paddlers who were right behind them or to male paddlers with far less experience. Those comments just reinforced their resolve to push on.

“I want people of color to feel safe on the water,” Cory said, “to feel welcome on the water. And I want them to see themselves in me.” Cory is doing just that, a living example of a woman of color facing all that the river has to offer, getting a helping hand and coping with the occasional prejudices, and pushing on to finish an epic journey.

Follow their journey at: https://www.women-on-the-water22.com/

Fiona Fordyce

Tags: guide, paddling, tourism, Midwest tourism, campfire cooking

Fiona Fordyce is no stranger to big rivers. She grew up near the Missouri River just upriver from its confluence with the Mississippi. “We were tossed in the river as babies,” she joked. As a child, she and friends would hop into inner tubes and float down the Missouri River to Pelican Island where they’d search for arrowheads before floating on to Sioux Passage Park. “I always thought that it was really fun.”

When she was a little older, she took friends paddling from her home to Sioux Passage. They were amazed at the experience, felt like the paddle on the big river was a real novelty, and loved it. Maybe that’s where her guiding career started.

She went on to college intending to pursue a career in science, but after graduate school and all those years of hard work, the thought of working in an office or lab wasn’t appealing. She needed a break. She took a job guiding people around national parks with the expectation that one year would be enough. She led camping and hiking trips in the US. Then she got the chance to lead luxury tours in Chile, Mexico, and Colombia. One year turned into ten.

Nine years ago, she joined Big Muddy Adventures (BMA), part of the core group of three dreamers working to get more St. Louisans on the region’s big rivers. While she guided some trips, she soon settled into the niche of sandbar chef, especially after she came up with the idea of a rivertime supper club. BMA transports people in voyageur-style canoes to an island or sandbar where they hang out and eat a good meal. Fiona preps and cooks the food using locally-sourced ingredients, and the cooking is finished on site, campfire style. The trips always sell out and attracts a long waiting list. A food journalist who went on one of the trips called her “… one of St. Louis’ brightest rising culinary stars…”

All the hard work and promotion from BMA is paying off. In 2022, they took about 3,000 people on canoe trips, which is nearly 10 times the number they guided just three years ago. In the process, they’ve opened up a lot of minds.

“Everyone thinks about the river as polluted and toxic, you know, something gross, but I think that Big Muddy in the last few years has done a great job of changing people’s perspective on that.”

The beautiful sandbars surprise people: “Oh my god, this is like a beach!” Many of the paddlers are surprised to find natural places so close to the city. “I like that we have this really unique outdoor rec opportunity here. It’s just so close to the city and you can feel like you’re far away and in nature.”

Most of the BMA trips are a few hours long, but Fiona hopes the company will offer more overnight trips in the near future, to give more people the chance to fully immerse in the world of the Mississippi, to better appreciate our own big river. It happens in other places, after all. “The Amazon is a huge attraction. People fly to South America to see the Amazon. They fly to Europe to see the Danube… The Mississippi competes with those rivers easily.”

Guiding hasn’t detracted from her own joy of being on the Mississippi. She’ll still go out occasionally to explore. “I like going on the river on my own, but it’s even more fun to show people this thing that they didn’t know was there… Everyone leaves saying ‘I have no idea this was here.’”

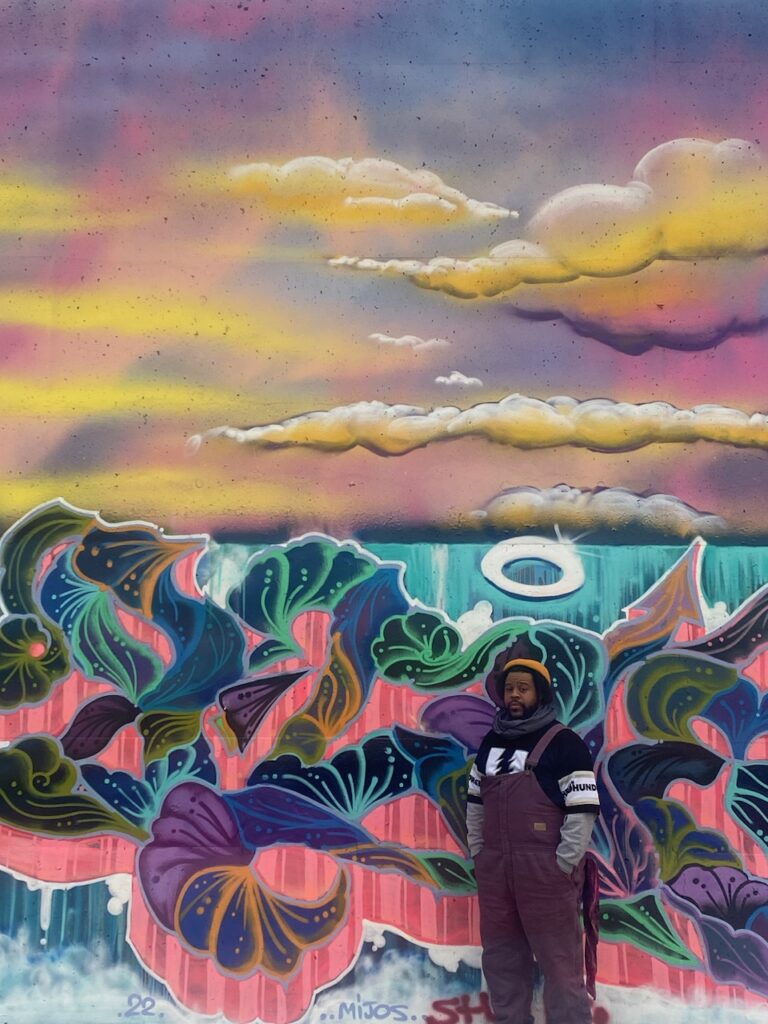

Jamaal Hodge

Tags: fishing, graffiti art, inspiration, life lessons, creativity

Some experiences leave a lasting impression. For Jamaal Hodge, a childhood trip to the Mississippi River in St. Louis and a moment, a first glimpse at striking pieces of art, catalyzed an interest in art that shapes his life to this day.

That first trip to the Mississippi had nothing to do with art, actually. His stepdad took him to the river to fish, to get to know each other, really. Jamaal was seven years old—had never been to the Mississippi before—and his stepdad was new to the family. His stepdad loved the outdoors and wanted his stepsons to develop the skills to fish and hunt.

They drove along the city’s flood wall until they found an opening they could pass through. On the bank of the Mississippi, he and his brother assembled their poles, their stepdad patiently correcting each mistake. They found worms for bait underneath rocks and learned how to get them on the hook. Jamaal found it boring at first. They’d spend a few hours at the river and he and his brother would leave empty-handed, while their stepdad reeled in five or six catfish.

“… it [fishing] requires a decent amount of patience, and I think that’s what he was trying to teach us.”

Their stepdad bought them fishing gear and slowly revealed a few secrets. “We ate every fish he caught. He taught us how to descale them. He taught us how to get the bone out of them. He actually taught us how to fillet them, too. It was my first time working with a knife as a child.”

His stepdad once caught a pregnant fish and threw it back. “It was one of my first memories of compassion I would say.”

They made those trips to the river for a good four years. “It [fishing] basically just taught me to observe my surroundings and to be present, ‘cause when you’re fishing, you have to be present. It’s just you and the river.”

That time next to the river did indeed bring them closer. “I got to see him as a human, not just my stepfather, and that was something beautiful that he gave us.” It helped Jamaal see him in an entirely new way. “It was the most peaceful I ever saw that man [when he was fishing]… He was at ease when he was fishing.”

Still, fishing isn’t the most prominent memory from those trips. “You drive down there [to the river], and you see this large wall of just graffiti and art, and this was my first interaction with graffiti.” The flood wall was decorated with graffiti that had been painted on the wall as part of the city’s annual festival known as Paint Louis. Artists from around the country flocked to St. Louis to turn a drab, grey concrete wall into a canvas covered with vibrant images.

Jamaal had already taken an interest in painting and drawing by then, but the scale and style of the art on the flood wall were entirely new and captured his attention. “I’m in awe, I’m captivated at this point… It’s like the first thing I remember of going to the Mississippi.”

“It was the first time I’d even seen so much color, like on anything.” The images popped against the gray concrete background and the factories and railroad tracks. Before they fished, he and his brother would walk along the wall to check out the art. When his mother came along, he’d show her his favorites.

“That wall means so much to me.” He fell in love with the angular forms of the letters and characters, the striking use of color, and the depth of the imagery. One eye-opening piece was done solely in different shades of blue.

“To this day, that is the main reason I started doing art. I do not consider myself an artist, but I do consider myself a creative. That is one of the key starts of me becoming creative and wanting to learn something, being passionate about learning something. It triggered that for me.”

Jamaal had a speech impediment when he was young and a learning disability. Words were not his thing. Fishing provided experiential learning, forced him to slow down. Graffiti art triggered a way for him to express himself.

Today, he’s a musician, albeit one who also sketches and paints at times, too. During an earlier stage of his music career, he sang in Carnegie Hall with a choir. Today he’s part of a music collective called Kin Folk that focuses on creating an ecosystem where musicians can support each other and thrive.

And those trips to the Mississippi River helped kick start it all. “Those are some of the most prominently memorable moments of my childhood… I have very fond memories of the Mississippi.”

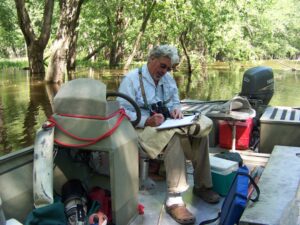

Jon Stravers

Tags: birds, music, veteran, spirituality, peaceful, calming, hawks, warblers, conservation

The Hawk Man of Iowa is a title that one doesn’t acquire casually. Jon Stravers earned it because of his dedication to studying and understanding the lives of Red-shouldered Hawks. That work wasn’t part of any grand plan he’d had for his life.

He served in the Navy during the Vietnam War and felt out of place when he came back. “I didn’t necessarily adjust too well to society when I came back from Vietnam,” he said, “and so my solution was to escape, escape in a canoe. And it was then that I started this connection with birds and trying to figure out what everything was… I just worshiped the idea of being quiet and on the water.”

The water was a natural draw for him. His father was a fisherman. “I grew up with a reverence for wood boats and low motors and quiet and the water.”

Through his burgeoning interest in birds, he connected with Gladys Black, the “bird lady of Iowa” and found himself a new career. In 1976, he got involved with a raptor research project in the Mississippi River bluffs, then started studying raptor migration, something he is still doing today. In 1978, he began following the nesting behaviors of Red-shouldered Hawks in floodplain forests and, again, is still doing that today. After decades in the field, he has a pretty good understanding of Red-shouldered Hawk communications and can even identify individual birds from their calls.

In 2006, he noticed that the areas where he was working also seemed to attract a lot of Cerulean Warblers, an observation that no one else had made. The birds were in some trouble because of habitat loss. His work soon revealed that a large cluster of Cerulean Warblers nest in many of the same forests as Red-shouldered Hawks and that many return every year to those woods from their winter homes in South America. Because of his observations, parts of northeast Iowa were declared a Globally Important Bird Area.

Jon’s home territory covers a part of the river around McGregor, Iowa—thick backwater forests bisected by small side channels, tall bluffs, and gravel terraces built by deposits from glacial meltwaters that barreled down the engorged Wisconsin River.

“There’s so much diversity on the river, I mean, when you’re on the main channel it feels one way, but it certainly feels a lot different when you back in a small little channel, back in the woods when it’s flooded in the spring. It’s a whole different thing… “I’m a lucky person to be able to work on what I love and mess around in the floodplain forest.”

Jon also earns part of his living as a musician. He plays with a band called Big Blue Sky and is a regular presence on the Maiden Voyage cruises out of Marquette, Iowa. They have ten CDs of original music to their credit, much of it written about the river or birds and a spiritual connection between people and the natural world. The band plays a few concerts a year to raise money for one of the non-profits that supports his work, Driftless Area Bird Conservation.

Jon doesn’t take any of this for granted. He feels lucky to have found a place where he belongs, where he can feel “… the wildness of the backwaters and the side channels… I was lucky in that I recognized this was what I wanted to do, and I was lucky that I was able to find the right people around me to help me keep going.”

For the Hawkman of Iowa—Hawk Daddy to his grandchildren—the area where he works is a special place. “I think of it as a cathedral, and I’m in the cathedral, so it’s my work but I think it’s sacred.”

Driftless Area Bird Conservation: https://driftlessareabirdconservation.com

Big Blue Sky: https://bigbluesky-dabc.com/

Pheng Xiong

Tags: fishing, calming, peaceful, veteran, conservation

For Pheng Xiong, fishing in the Mississippi River isn’t just a hobby, it helps take the edge off of stress and anxiety that lingers from his service in the US military. And looking after the natural world just may end up being his professional calling.

“I’ve been fishing the Mississippi ever since I was a really young kid,” Pheng Xiong told me. “I’d say probably like 8 or 9 years old.” He’s 28 now. That’s 20 years of tossing a line into some part of the Mississippi River, mostly between St. Cloud, Minnesota, and Lake Pepin.

His father took him fishing the first time, around Prescott, Wisconsin, where the St. Croix River merges with the Mississippi. As a kid, he and his father were angling for black and white crappies, white bass, and walleye. He learned how to scale, clean, and fillet fish during those years when most of what they caught ended up on the family dinner table.

White bass, in particular, is a popular fish species for Hmong people. “It has a flaky texture to it,” Pheng said, “and it’s a little softer than crappies.”

These days he’s more likely to fish in the Mississippi around St. Cloud, Minnesota, where he’s studying biology at St. Cloud State University. “Fishing the Mississippi, there is so much range where you can fish, depending on the depth level and all that stuff and what certain type of fish you want to fish for. In the Mississippi, there’s so many different types of fish.”

While he may be trying to land a walleye, catfish, or white bass south of the Twin Cities, around St. Cloud, it’s all about the smallmouth bass, muskie, and northern pike. “Me, personally, I’m not really a big eater of fish… I’m really big on game fish, fishing for them for fun. It’s all about the fight… It’s more like a stress reliever for me.”

Pheng is also a military veteran. He served four years in the U.S. Marine Corps and struggles at times with anxiety, depression, and PTSD related to his service. “Just fishing within the Mississippi River has helped me tremendously to be able to relax, to not think too much about the situations that happened to me earlier… It’s just a great stress reliever for me to do something like, to just get out there and do it, make you feel like you’re useful, just go out and fish and relax.”

Pheng is preparing for a career in conservation, hopefully one that involves fish. He’s getting plenty of real-world experience along the way. Two or three times a week, you can find him on a riverbank or maybe in a canoe or kayak on the Mississippi with a fishing line in the water and a smile on his face.

The Pochés

Tags: paddling, river angel, lower Mississippi; Louisiana, giving back, community

There’s a hidden world along the Mississippi River, a network of folks who live along the river who are willing—eager, even—to lend a helping hand just because they want to. We call them river angels. If you’re a long-distance paddler, you already know about them. And if you’re one of those paddlers who has made it to Louisiana, you know about the river angels at mile 149: Trixie, Wayne, Charlie, and Doug Poché (poe-shay, if you plan on asking for them without getting hung up on).

The Pochés’ oasis is about halfway between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, in the middle of a busy industrial and shipping corridor that challenges the skills of the best paddlers. Flag poles help mark their spot on the east bank downriver of Stone Oil after the bend. If the river’s low, they have a nice spot of grass and shade under willow trees in the batture (the land on the river side of the levee) When the river’s higher, they shuttle paddlers in a golf cart over the levee to dry land. Adjacent to their property, you’ll also find a nice sandbar with a pond where a congregation of alligators live. “We tell them [paddlers] don’t go swimming in there,” Trixie said.

Trixie thinks the first time they helped a paddler was maybe 20 years ago, possibly longer, when friends of her nephew passed by on a long trip down the Tennessee, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers. Extended family and neighbors pitched in to feed and look after them. The number of through paddlers seems to have gone up in recent years, so it’s not usual if they see two or three groups a week during the peak season.

River angels will do just about anything to help other river people, especially paddlers: refill water bottles, take them to the store, feed them, help them dry out. When one long-distance paddler injured his back, Wayne drove him to a chiropractor.

One memorable summer evening a while back, the Pochés hosted ten paddlers at once, which included an older brother who was taking his younger brother on a long-distance paddle “… ‘cause he wanted to teach him that there were more things than sitting in front of the television with a remote,” Trixie recalled.

The Pochés and other river angels get nothing from this experience. Well, almost nothing. Trixie admits that helping river folks brings her joy, and more. “Like I say, it goes both ways. We learn a lot from them, also.” They’ve met paddlers from around the world and learned about their home cultures. They’ve met seasoned adventurers who shared stories of their experiences in remote parts of the world. They also get to introduce folks to a bit of their own culture, like the paddler who had never before eaten a po’ boy.

They’ve lost track of the number of paddlers they’ve helped, but many of them keep in touch. “That’s the good thing about it. I still talk with some of these guys on Facebook. We’ve had great stories from them, and they got stories from us.” A few offer thanks in their own ways, like a sketch made while paddling the river or a copy of a book they wrote about their experiences.

For a long time, the Pochés were the only river angels in the area, but they’ve since been joined by a handful of others nearby, which is a good thing. The Pochés, Trixie and Wayne in particular, are slowing down.

“Just recently I wrote a hard letter and told the guys I can’t do this anymore.” Her body is telling her to take it easy, maybe to spend less time hauling gear and cooking meals from scratch and more time sitting in the batture with a book and her dog, especially on those days when a light cooling breeze blows off the water.

Don’t fret, though, paddlers. The Pochés’ oasis isn’t going away. If she has food already cooked, she’ll be glad to share some. And other Pochés are stepping up to continue the river angel tradition. “Somebody will always be back there, and you can stop at river marker mile 149.”

Join our

COMMUNITY

And Get a Free E-book!

When you sign up as a River Citizen you’ll receive our newsletters and updates, which offer events, activities, and actions you can take to help protect the Mississippi River.

You’ll also get our free e-book, Scenes From Our Mighty Mississippi, an inspiring collection of images featuring the River.

Step 1

Become a River Citizen

Yes! The River can count on me!

I am committed to protecting the Mississippi River. Please keep me informed about actions I can take to protect the Mississippi River as a River Citizen, and send me my free e-book!, Scenes From Our Mighty Mississippi!

Step 2

LEARN ABOUT THE RIVER

We protect what we know and love. As a River Citizen, you’ll receive our email newsletter and updates, which offer countless ways to engage with and learn more about the River. You can also follow us on Instagram, Facebook, X (Twitter) , and YouTube, where we share about urgent issues facing the River, such as nutrient pollution, the importance of floodplains and wetlands, and bedrock legislation such as Farm Bill Conservation Programs.

Step 3

Take Action

There are many ways you can jump in and take action for a healthy Mississippi River. Our 10 actions list includes simple steps you can take at any time and wherever you are. Check out our action center for current action alerts, bigger projects we are working on, and ways to get involved.